19 Jan ARCHIVE CONNECTION ESSAY NO. 5 ZOE DUSANNE

“The Only One I Have”: Zoe Dusanne in the Archive

Richelle Munkhoff and Beth Ann Whittaker Williams

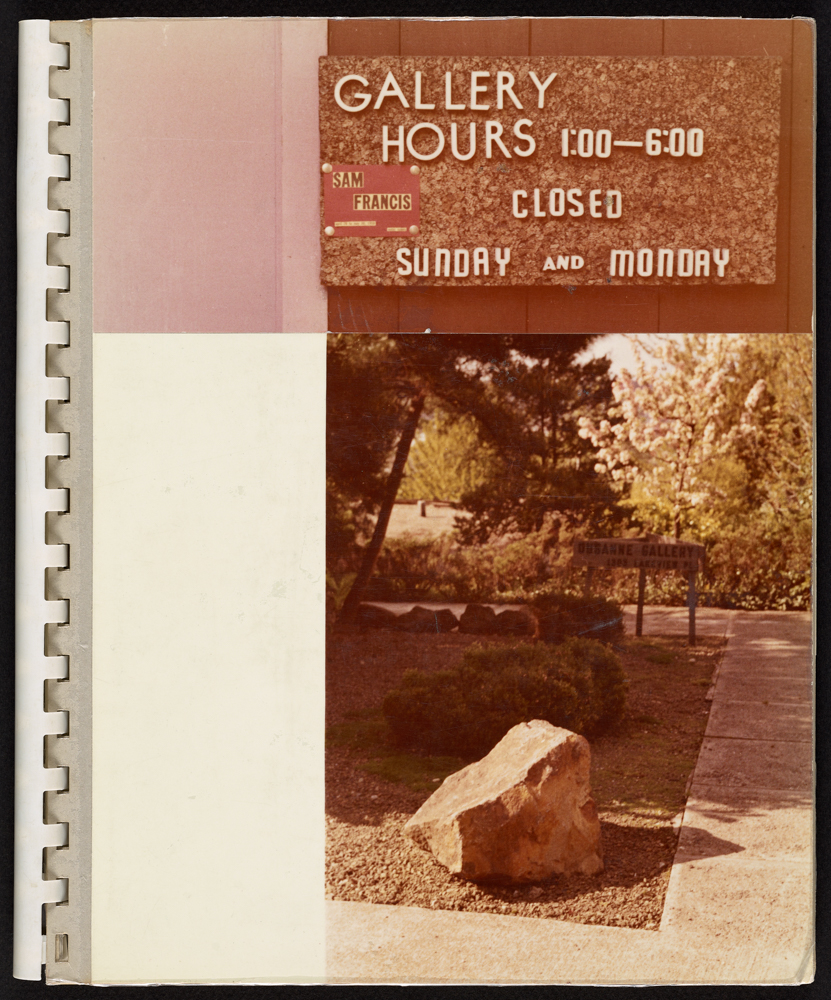

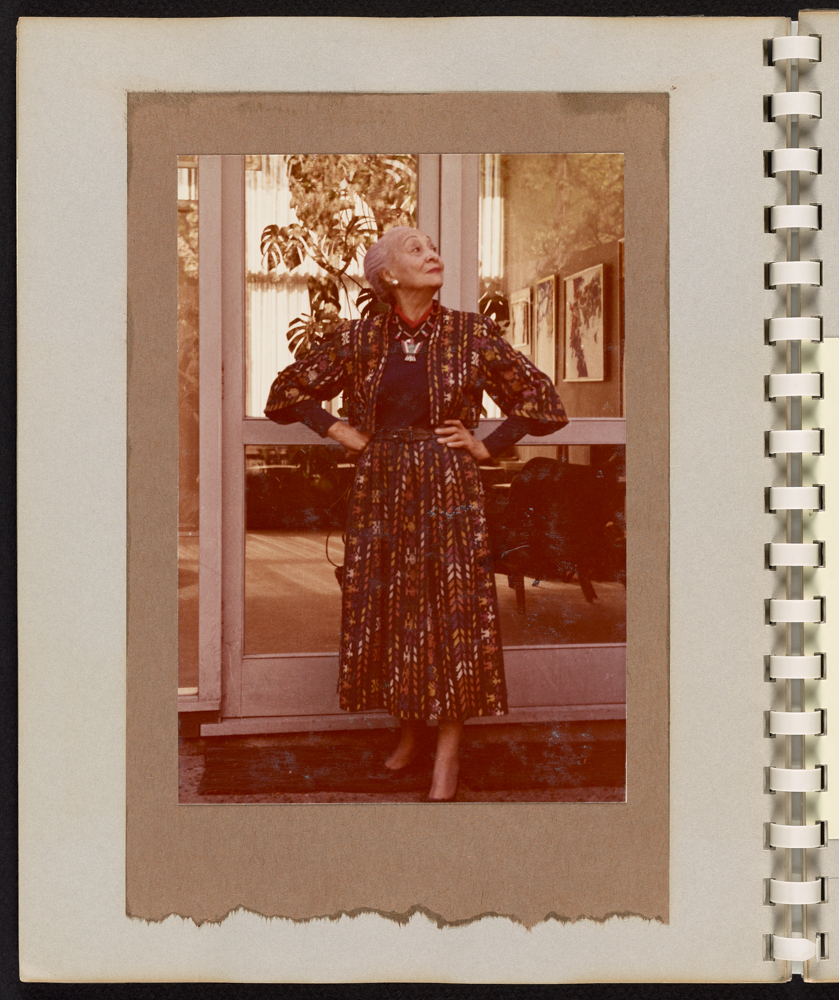

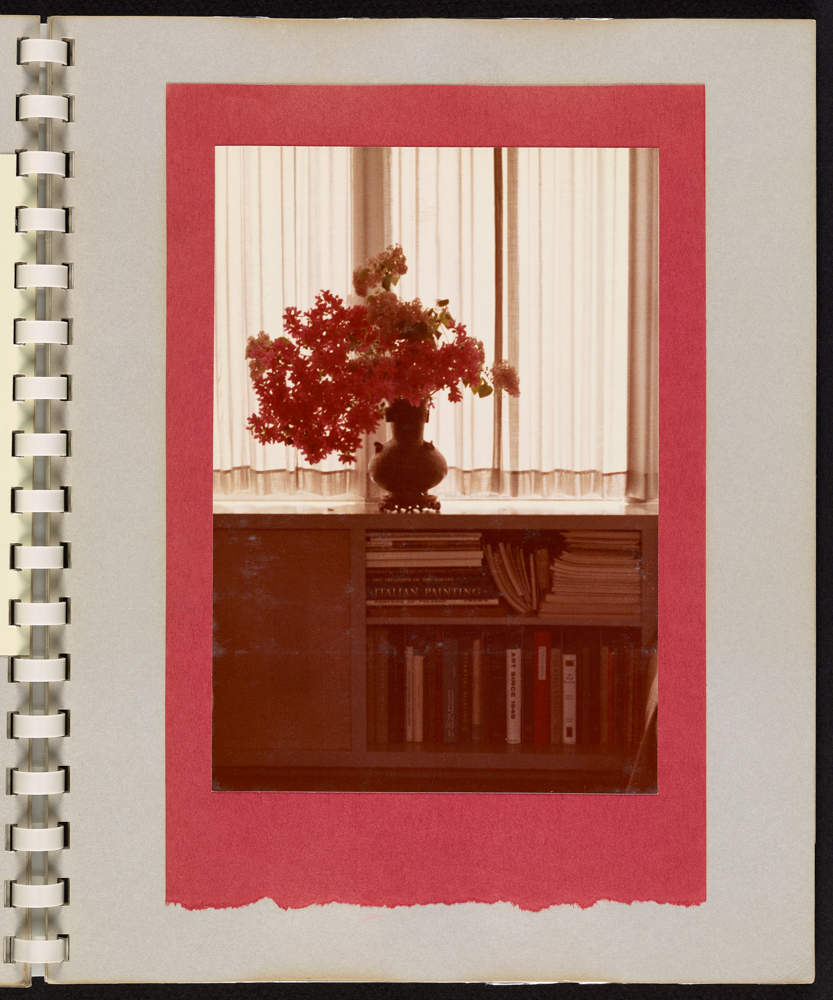

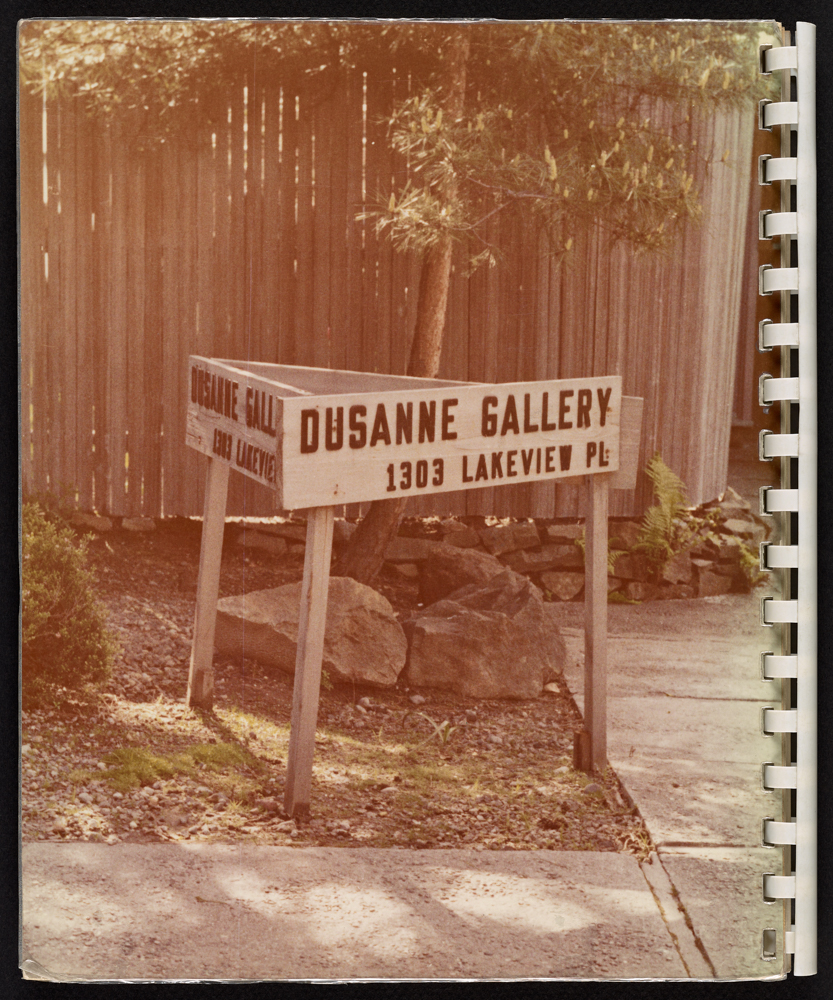

One of the most poignant pieces in the Sam Francis Papers now housed at the Getty Research Institute is a spiral bound collection of photographs Seattle art dealer Zoe Dusanne made of the final exhibit she held in her home gallery in the spring of 1959. It is not an exhibition catalog exactly, although the occasion was a Sam Francis show. Rather it is a testament to the space itself, scheduled for demolition that summer under eminent domain. The spiral booklet attempts to document the lived experience of the private and professional worlds Dusanne had created to such success – as those worlds were literally being stripped from her.

In this essay, we would like to circle around the spiral booklet to talk a little bit about the amazing woman who was Zoe Dusanne, and the significance of her gallery, to show why documenting it in the face of destruction was so important. Although legacy was a difficult topic for Zoe (for reasons we discuss below), she nevertheless created this ephemeral memorial to her gallery to mark her achievements. Because history is written from documents collected into archives, Zoe’s act of preservation becomes exponentially significant. She inserted herself into Sam Francis’s records with intention. She could not foresee that these records would end up at the Getty Research Institute, but she knew that Sam also valued legacy, and she trusted him with caring for a little bit of hers. And he did. We will return to the significance of the archive, and of legacy, but first we need to say more about Zoe Dusanne herself.

Zoe Dusanne (1884 – 1972)

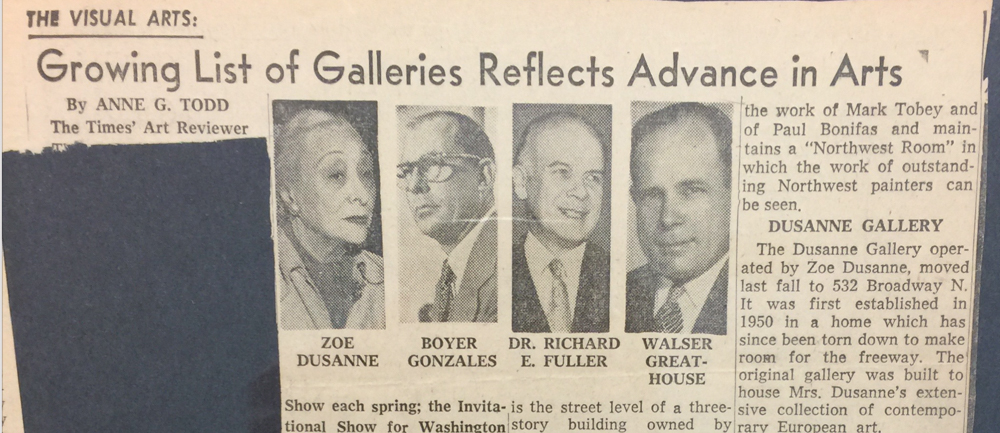

In November 1950, Zoe Dusanne opened the first private gallery devoted to modern art in Seattle. For several years prior, she had been showing her personal collection of nearly fifty works by contemporary artists amassed during her time in New York in the 1930s and early 40s. Modern art was still comparatively rare in Seattle at the time, and Zoe’s collection became an important gathering point for the regional art world. This salon experience inspired Dusanne to have designed and built a suitable structure to house her collection. The result was a modest mid-century home that integrated living and exhibition space, with soaring glass walls to take advantage of views overlooking Lake Union.1

From its opening, the Dusanne Gallery promoted Northwest artists and championed an international group of painters that included Americans working abroad. Zoe encouraged and supported then-emerging artists such as Paul Horiuchi, George Tsutakawa, John Matsudaira, and Kenjiro Nomura. For these men in particular, she did so at a time of rampant anti-Asian racism. All of these artists had been catastrophically impacted by President Roosevelt’s 1942 Executive Order 9066, ordering the incarceration of Japanese Americans on the west coast into concentration camps.

Zoe also supported more well known Seattle artists. In the early days of the gallery, Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson were promoted and at times represented; indeed, Zoe was instrumental to the 1953 Life magazine article that secured these “Mystic Painters of the Northwest” a national audience.2 A hub for introducing young international artists to the region and beyond, the gallery hosted the first US solo shows for Henri Michaux (1954), Paul Jenkins (1955), and – most famously – Yayoi Kusama (1957).3 Dusanne’s name has long held significance within Francis’s biography as the first gallery to offer him a US solo exhibition.4 Over the course of nearly two decades, Dusanne held four Sam Francis solo exhibitions and numerous group shows that included Francis.

If you have heard Zoe Dusanne’s name already, likely you know this much about her. If you have encountered further details about her life, possibly the fact that she and her parents were founding members of Seattle’s branch of the NAACP stands out. We first encountered Zoe Dusanne in the Sam Francis Papers where we were struck by the power of her voice in letters written to Francis in the 1960s when they had known each other for about a decade. The letters were few, contained in a single folder. Yet here was a woman who at sixty-six decided to embark on a new career. A woman who had been a prominent member of Seattle’s Black community in 1913, but who was not – publicly – a Black woman in 1950. In the Getty’s reading room, a woman born in the 1800s was speaking evocatively to us in the 21st century about the complicated histories of race and gender in America. We listened – and we wanted to know more: how did Zola Maie Graves Young become Zoe Dusanne?5

Here is an overview of our much longer project.

Becoming Zoe Dusanne

Zola Maie Graves was born in Kansas in 1884. Her father had almost certainly been born enslaved, although we have yet to find much about his life before 1870. Her mother’s rich family history would have been well-known to her. Her grandfather, George Henry Dennie, fled the plantation in Virginia where he had been enslaved, and built a prosperous life with his wife Martha Murphy Dennie, first in Illinois, then Kansas, and later Oklahoma.6 Throughout her life, Zoe was close with many maternal relatives who lived scattered across the Midwest and West. These facts are not part of the public stories Dusanne told about herself in later years.7 But they definitely shaped her as a woman, a Black woman, an entrepreneur, and a patron of the arts.

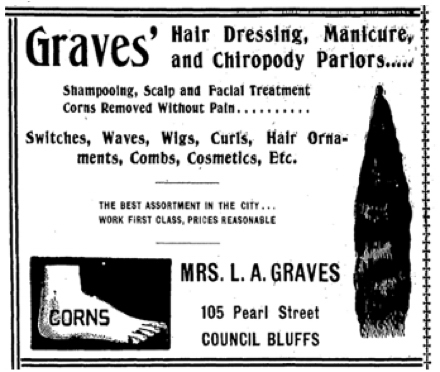

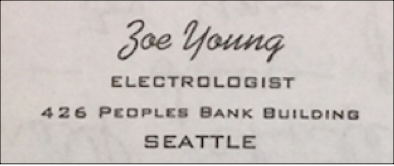

Zoe grew up working in the family business, a hair salon, work done by both her mother and grandmother, and work she would do throughout most of her career. Zoe Graves briefly attended Oberlin and the University of Illinois. She married and had a daughter. The Graves family eventually moved the hair and chiropody (podiatry) business to Seattle.8 Newly divorced and a single mother, Zoe Young joined them there in 1912, when she was 28, opening an electrolysis salon.

The Graves family became prominent members of the growing Black middle class. Zoe and her parents were founding members of the Seattle branch of the NAACP in 1913. Letitia Ann Dennie Graves, Zoe’s mother, was elected its first President. In 1915, Zoe Graves Young is listed as Recording Secretary.9

Zoe’s daughter Theodosia trained as a dancer and actress at Seattle’s Cornish School. Through the school, Zoe met artists such as Mark Tobey. There Theodosia garnered recognition and success, but some white parents complained when the Graves family attended performances.10 Racism limited Theodosia’s career opportunities in Seattle, so when she graduated in 1927 she set her sights on Broadway.

Mother and daughter arrived in New York in 1928 with the stage name Dusanne – a name Zoe would retain.11 During the Depression, Zoe worked with her hands as she always had, money was tight. She worked for the WPA, making puppets. She was also deeply involved in the theater world – sewing costumes, creating wigs and props for productions, including the Tallulah Bankhead production of Antony & Cleopatra (1937).

Arriving in New York at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, the Dusanne women chose to base their new life downtown, centered on “Romany” Marie’s Tavern in Greenwich Village. Mark Tobey had given Zoe an introduction to Marie Marchand, and Zoe was to become a “devotee.”12 Dusanne immersed herself in the artistic milieu of the Village, which of course overlapped with those of Harlem and other communities. From the moment she arrived, artists and intellectuals – including Stuart Davis, Joseph Stella, and Buckminster Fuller – were her neighbors and friends. In the fourteen years Zoe lived in the Village – years that spanned from the Depression to the outbreak of WWII – she would learn the importance of tangible support for struggling artists, and the difference such support made, whether physical, emotional or financial.

Zoe worked with Marguerite Zimbalist in her Ten Dollar Gallery which was dedicated to supporting artists during the Depression. Zimbalist encouraged people to buy on installment. This is exactly what Zoe did – she would pay $1 a week, saved by giving up other things. Later she would say: “Some of the artists who had paintings for sale at that time you wouldn’t believe, but as you know artists are the first to feel the pinch of hard times and they were letting their things go so cheap.”13

Zoe Dusanne returned to Seattle in 1942 with almost 50 pieces of modern art. Initially, she had no plans to open a gallery or become a dealer, but her important personal collection drew her increasingly into Seattle’s art world. Those circles did not know of Zoe’s earlier life in Seattle — and she did not correct their assumptions. Under the name Zoe Young, she resumed operation of her electrolysis salon, alongside the Graves’ chiropody business. She would continue to derive her income from this occupation for the next decade. Whether or not she fully intended it, the two names allowed Zoe to maintain a bifurcated identity for the rest of her life: Zoe Young, who had a long history and strong connections in Seattle’s Black community; and Zoe Dusanne, a glamorous assumed-to-be-white newcomer to the regional art world.

Bifurcation of her identity meant Zoe could have an important public role in the arts that likely would have been denied her if she had been open about her full identity. In 1947, the Seattle Art Museum exhibited “The Zoe Dusanne Collection” – a rare honor for a woman collector. Would it have so honored her as a Black woman collector? Similarly, since she acquired art mostly by white men, Zoe has a complicated place in the history of African American patrons and collectors.

On her own terms, the Dusanne Gallery was a success. Perhaps not financially, as she always struggled in an art market that did not yet appreciate these works – neither aesthetically nor economically – as they are now valued. Yet Zoe’s influence and impact continue to this day. She was “the vital catalyst in the cultural life of this region.”15 Many pieces from her personal collection, or purchased through her gallery, remain in the region’s museums, including the Seattle Art Museum and the Henry Art Gallery.

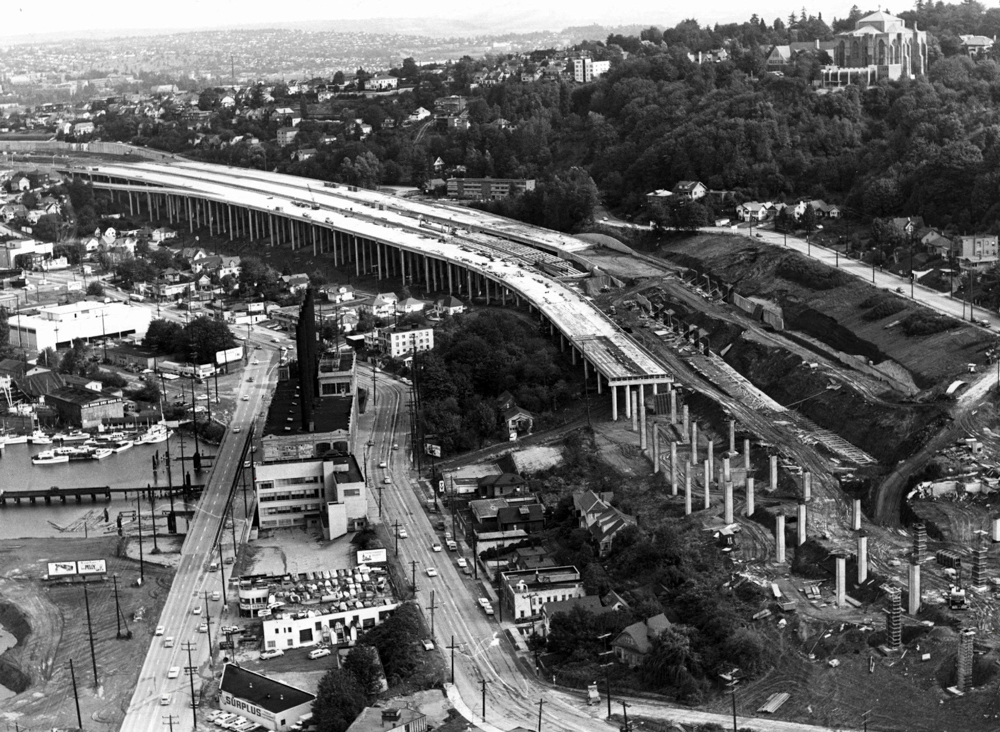

Zoe’s architectural “gem” of a home and gallery at 1303 Lakeview Place existed for little more than a decade. The success of the gallery could not prevent the march of progress. In 1958, Dusanne was informed that the government would be invoking eminent domain in her area of Seattle in order to build what would become Interstate 5. This process was happening across America, too often razing communities of color in the name of expedience.15 In Seattle, Zoe’s fate was tied to geography. She had chosen to build on the small strip of land above Capitol Hill, between Lake Union and Volunteer Park. Interviewed by Time magazine: “The uprooted may agree with Seattle Art Dealer Zoe Dusanne, whose home and gallery overlooking Lake Union will soon disappear before the Everett-Seattle-Tacoma Freeway. Says she: ‘I am a great believer in progress. But what a pity progress has to cost so much.’”16

It’s within this context that Dusanne hosted her final exhibition – Sam Francis – in April/May 1959. And it’s within this framework that we should understand the significance of Zoe’s spiral-bound collection of photographs. For while some images do display Francis’s artwork in situ (as in figure 2 above), many simply show corners of her home as she created them, documenting her life as it was – the odd and delightful details of a beloved home about to be destroyed.

The destruction of Dusanne’s home and gallery at 1303 Lakeview Place was not the end of the Gallery itself. By the fall of 1959, Zoe had made the “wrenching” move to an apartment at 532 Broadway and reopened the Gallery.17 She tried to regain momentum, but at 75 years old, starting over was difficult. The spiral-bound booklet remained with Zoe through the transition, carrying with it her memories of the space and community she had built in Seattle’s art world. In 1961, with legacy clearly in mind, she gifted the spiral book to Sam Francis. In early 1963, Zoe suffered a stroke. She closed the Gallery and retired in 1964.

In a 1961 letter accompanying the booklet, Zoe Dusanne tells Sam Francis:

“The inclosed [sic] photographs are of my gallery which were taken during my last exhibit (yours) in ‘58 as you can see. That’s the only one I have and the man charged me quite a bit. However, I am sending it to you because I love you but never let it get out of your hands as I had intended to keep it, but I want you to have it.”18

The preservation of this piece was vital to Dusanne. Not only the item itself, preserving the images of her home and all she had constructed, but also the preservation of her legacy. Sending this to Francis was an interesting choice, whether consciously done at the time, as his papers now exist in a protected space with privileged access.19

Housed at the Getty

The precious collection of photographs bound in a spiral booklet sent from Zoe to Sam as an act of love and trust is now housed at the Getty Research Institute, Special Collections, Sam Francis Papers (M8.2004) within Box 249. It is protected and secure.

It is also invisible.

Currently, if you search for “Zoe Dusanne” in the Getty research catalog, you will not find her listed in the Sam Francis Papers. Because her name is not designated in the finding aid, she seems not to exist in the record. She’s not the only one. It’s simply a fact: there is rarely a full index of names in any finding aid. Someone – many someones – are always left uncatalogued.

Archival pieces, who views them, and what they see quite literally makes history. Who has access to the privileged spaces of the archive shapes the narratives told. The hierarchies of privilege within the archive also make it difficult to find the documentary traces necessary to telling a wider and richer history, especially of lesser known individuals – too often women and people of color.

Zoe’s booklet is in the archive and if one is lucky enough to stumble upon it, the history of Zoe Dusanne lives on. We are now working on a fully expanded biography of Zoe Dusanne having scoured many other archival holdings. But throughout this research journey we came to see that there are so many other people similarly situated in the archive. From this experience, Plain Sight Archive emerged. A non-profit organization with the mission to activate the archive, to elevate figures who are hiding in plain sight.

In 2022 we attended virtually the Duncan Phillips Lecture given by Dr. Elizabeth Alexander, Poet, and President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.20 Toward the end of the Q&A, she said something that crystalized for us our mission: “From wherever we sit, there are ways that we can see more inclusively. So to me, the question is always: from where you sit, what will you do?”

We are privileged to sit in archives, searching for the overlooked, uncatalogued pieces that exist in the archival record. Information that is hidden in plain sight – but that needs to be elevated in order to be seen by others so that more inclusive history can be written. It’s where we sit. It’s what we can do.

Richelle Munkhoff is a freelance archivist and writer based in Boulder, Colorado. She has 25 years’ experience working in archives, post-secondary education and research institutions. With a PhD in English literature, she has challenged institutional boundaries, telling new histories based on material hidden in plain sight.

Beth Ann Whittaker is Associate Director of the Sam Francis Foundation in Los Angeles. She has 18 years’ experience working in archives, catalogue raisonné, legacy building, working with museums and galleries, and community outreach to widen the voices active in the art world and non-profit arts sector.

Together they have launched Plain Sight Archive, a non-profit organization dedicated to fully inclusive history in 20th century visual arts and culture. The mission is to build an innovative relational archive that illuminates and connects traditionally obscured figures and creative communities. This vision includes foregrounding narratives that highlight expansive representation in the arts, now and for the future.

Notes

[1] Seattle architects Bert Tucker, Robert Shields and Roland Terry designed Dusanne’s 1000-square-foot home and gallery at 1303 Lakeview Place. Construction began in March 1948.

[2] [Dorothy Seiberling,] “Mystic Painters of the Northwest,” Life (28 September 1953): 84-89.

[3] Zoe not only was the first to show Kusama in the US, but she also had an important role in securing the visa that allowed Kusama to remain in the US.

[4] Dusanne offered Sam Francis his first US solo show in 1956 (March 14–April 7, 1956), but Martha Jackson pulled off an earlier date by one month (February 14–March 3, 1956).

[5] Primary research on Zoe Dusanne’s career and life starts with Patricia Svoboda, “Zoe Dusanne: Seattle Art Dealer, from 1950 to 1964” (Thesis for Master of Arts Degree, University of Washington, 1980); Esther Mumford, “Zoe Dusanne: Pioneer Arts Advocate,” Seattle Arts 14.3 (March 1991): 4-7; and Jo Ann Ridley, Zoë Dusanne: An Art Dealer Who Made a Difference (McKinleyville, CA: Fithian Press, 2011).

[6] George and Martha Dennie had ten children. Together the Dennie family accomplishments and experiences tell American history from slavery to Civil Rights. For one piece of this story, see Alfred Stanley Dennie’s 1994 oral history housed at the Oklahoma Historical Society H2012.099.001.

[7] Papers deposited in the University of Washington archives by her daughter’s estate well after Zoe’s death contain numerous family photos from the mid-19th century through the 1950s. No family narrative exists in this archive, however. While Dusanne provided some details in interviews with journalists during her gallery career, at that time she was at pains to obscure her family’s history. UW: Zoe Dusanne Papers, 2430-004.

[8] Zoe’s mother trained in chiropody in Chicago in the 1890s. Giles Graves (Zoe’s brother) trained around 1930 and ran the business, no longer a hair salon, with his mother until her death in 1952, and then alone until he retired in 1976. Giles Dolphin Graves [and Daisy Graves], interview by Esther Mumford. Washington State Oral/Aural History Program. 1 October 1976.

[9] The Crisis, April 1915, p. 306.

[10] Ridley, Zoë Dusanne, p. 17.

[11] During her lifetime, Theodosia Young would account for her mother’s surname by claiming that Zoe was briefly married to a Henri Dusanne in the 1930s. We have no direct evidence that Zoe herself made such claims. We have yet to find any documentation of such a marriage, nor any record of a Henri Dusanne. Further, the timeline of evidence produced by our research demonstrates such a marriage was highly unlikely – Zoe and Henri would have met, married, and separated within a few months, without anyone else in their circle having met him. Most conclusively, Theodosia herself used the stage name Dusanne for most of her theatrical career from the late 1920s through the 1930s.

[12] Robert Schulman, Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village (Louisville, KY: Butler Books, 2006), p. 18.

[13] Zoe Dusanne,”Notes on a Collection,” p. 2. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Zoe Dusanne Papers, 2430-004, Box 2, Folder 1.

[14] Sarah A. Clark, “Introduction,” in A Tribute to Zoe Dusanne. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, March 24-May 8, 1977. Exhibition catalog.

[15] Indeed, Zoe’s uncle’s house in the Rondo Neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota was demolished to build I-94. Isaac Dennie was no longer living by the late 1950s when construction began, but his heirs were displaced and much of their thriving community destroyed.

[16] “Highways: The Great Uprooting,” Time, March 24, 1958, p. 26.

[17] Ridley, Zoë Dusanne, p. 105.

[18] May 7, 1961 letter from Zoe Dusanne to Sam Francis. GRI, Sam Francis Papers, Box 38 F17. Zoe misremembered the date of the exhibit; it was 1959.

[19] The booklet may have ended up in the Zoe Dusanne Papers at the University of Washington, but it just as easily might not. Neither Zoe nor her daughter Theodosia were directly involved with the donation(s). Several important items seen by earlier scholars do not seem to be in the UW archives. Nevertheless, we are very thankful that A. J. Kollar, a Seattle art consultant involved in appraising Theodosia’s estate, personally delivered the papers he found to UW. See Ridley, Zoë Dusanne, p. 126.

[20] The Phillips Collection, Duncan Phillips Lecture, 27 January 2022. Dr. Alexander’s lecture was recorded and can be seen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0CNDvEzsDE

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.