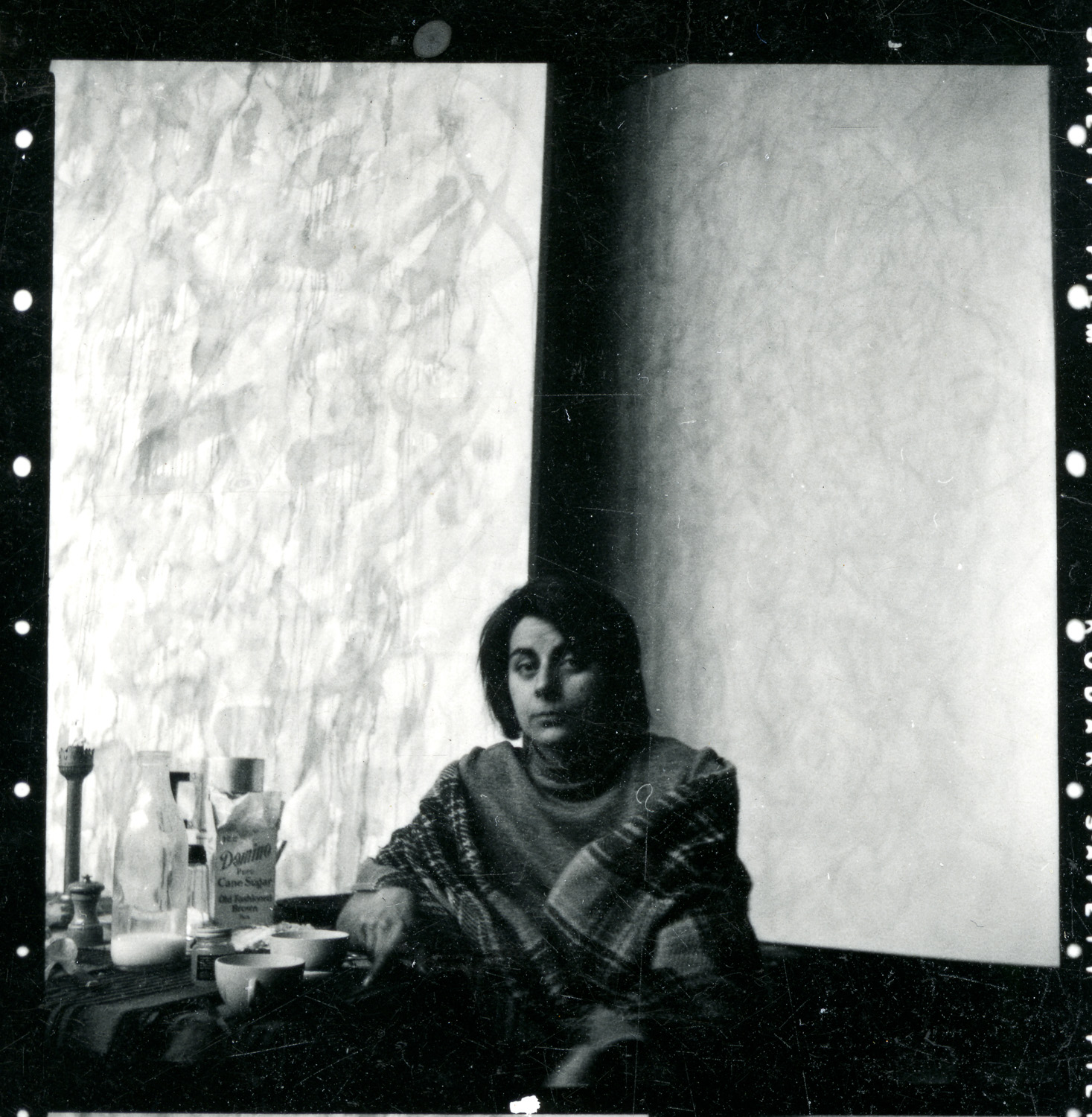

24 Oct ARCHIVE CONNECTION ESSAY NO. 4 RACHEL JACOBS

Elizabeth Buhe

When a young Sam Francis arrived in Paris by ocean liner in October 1950, he followed philosophy student Rachel Jacobs by a few short months. She came from New York while Francis came from San Francisco, but both ended up in a small expatriate community centered along the Boulevard Saint-Germain on the French capital’s left bank. There they formed a fiery and mutually-supportive cohort of writers, painters, sculptors, and philosophers that included artists Shirley Jaffe (see archive connection essay 1), Al Held, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Norman Bluhm, Claire Falkenstein, and Muriel Goodwin; critics Georges Duthuit, Yvonne Hagen, and Annette Michelson; and by 1955, painter Joan Mitchell. Jacobs found a studio at 11 rue Visconti and Francis found one at 52 rue de Seine. Later, Jacobs’s longtime apartment at 22 rue du Dragon was literally across the street from Galerie Nina Dausset, sometimes called la dragonne or Galerie du Dragon. Since all these sites were in a radius of several blocks, Galerie Dausset may be where the painter and the writer inaugurated an important intellectual partnership that would last over fifteen years. Here, in 1952, Jacobs could have seen Francis’s first ever solo show. He exhibited highly-regarded canvases brimming with washy stains in reds, blacks, and off-whites that overlap and press against each other ever so gently. Francis returned to the gallery for a group show of works on paper in 1953, this time accompanied by Bonnard, Dufy, Klee, Matisse, Riopelle, and others.

In the course of researching and writing my book on Francis’s painting from 1950 to 1970, I came to realize that Jacobs is one of the most significant commentators on Francis’s early painting, and I have spent years searching European and American archives for traces of her life and work. I learned that she came to Paris to study with the Hegel scholar Jean Hyppolite at the Sorbonne. Crucially, she also took classes with Maurice Merleau-Ponty at the Collège de France that significantly shaped her thinking and, eventually, with Roland Barthes. This direct contact with contemporary philosophy gave her a unique perspective on painting. Jacobs was one of the only thinkers within this young expatriate community who attempted to test philosophy against painting and vice versa, though of course the elder Merleau-Ponty and other phenomenologists of his generation wrote about painting.

While Jacobs penned only a few published pieces of art criticism, several of her texts address Francis’s exhibitions in the mid-1950s, and these press his canvases through a phenomenological lens. As I show in the book, Jacobs argues that the paintings Francis made in Paris enact the contextual structure of perception by demonstrating the way that everything in embodied vision is entwined. She believed in rooting her analysis of art not in the abstract rules of science, but in lived experience. As she wrote to her friend the art critic Yvonne Hagen, “every philosophical position must also be abandoned, if no position can be corrobarated [sic] in experience.”1 In the United States, Jacobs had studied logical positivism, but her investigation of aesthetics in France coincided with an intellectual shift away from the analytic tradition toward continental philosophy.

Jacobs’s correspondence offers glimpses of the friendships and collaborations of her life in Paris in the 1950s and 60s. The city, she reported to her brother Henry with characteristic wit, “is very Paris and very winter,” while in the classroom Hyppolite “pounds the desk furiously, with a kind of savage triumph.”2 Recalling the early days with prose that encapsulates an optimistic ambition, Jacobs recalled that “many years ago when I lived on the rue Bonaparte and first started writing in the mornings (instead of going to the Sorbonne) I would walk from the rue Bonaparte to the Observatoire around noon-time and have lunch with Sam near his studio up there and we would shriek at each other with excitement, day after day, and we were terribly convinced that the world was our oyster.”3 Clever turns of phrase signal plentiful inside humor. Her letters to Francis sometimes address him as “Ahab,” while Jacobs signs off as “your affectionate crocodile,” perhaps alluding to the inverted power dynamic between Ahab’s pursuit of Moby Dick and the crocodile’s pursuit of Captain Hook, which Melville’s tale inspired.4 Until 1963, Jacobs’s owned Francis’s painting Other White SFF.107 (1952), now in the collection of the Centre Pompidou.

Jacobs was enlivened by the energy of the Parisian art scene, which fueled her on-again off-again relationship to writing about art. Speaking of Mitchell and Riopelle—“saw Joan and Jean-Paul later, gnash, crash, bang”—she concluded that “now I want to start ‘art-criticism’ again.”5 Francis admired her writing enormously, even instructing his gallerist Martha Jackson to commission catalogue essays only if authored by Jacobs. In Paris, Jacobs befriended the painter Irving Petlin and his family. With Mark di Suvero, Petlin initiated the Los Angeles Peace Tower (1966) to protest the Vietnam War, for which he received letters of support from Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, and in which Francis included an artwork. Curious about what critics were saying in New York, she wrote to her brother asking for any clippings that seemed “reasonable,” “clear, intelligent—no phony poetry—not [Kenneth] Sawyer, not Dory [sic] Ashton, not [Clement] Greenberg,” perhaps signaling her own intellectual orientation away from the “tough-mindedness” of New York formalism.6

In turn, Jacobs’s support of Francis’s work opened doors. “Still on account of the things I’ve written on Sam, people have asked me to write for them. One of the editors of Art d’Aujourd’hui has asked me to collaborate (review, notes etc) and I agreed to do one article, but don’t want to get too involved.”7 Jacobs, ever the skeptic, was reluctant to give herself over wholly to the commercial art world’s demands. She liked to think outside the box. In a gesture we might consider proto-feminist, Jacobs co-authored a satirical text called “The Delinquent Academy” about the masculinism of New York abstract expressionism with Hagen that was published in 1958.8 Perpetually at work on larger projects about philosophy, “an excruciatingly funny idea” for an art text would come to her, and she would pitch it to an editor. Yet “I don’t like writing articles unless they are ordered,” she demurred.9 Many of these projects remained unfinished; she had “great difficulty in writing in Paris. An old trouble.”10 Francis offered to secure her a teaching post in California, but ultimately she felt she did not fit in the academy. Jacobs sparkled with ideas grander than she could realize.

Frequently, Jacobs traveled to Aix-en-Provence where the rural vistas revived her spirit, about which she wrote beautifully: “that subtle second growing period has come to the Midi after the autumnal rains, the young wheat is pure emeralds and mosses gleam; wild-flowers are growing in the vines, and the sun is low on the horizon, giving the sense of perpetual morning. . . . the pine clusters and the marvellous [sic] stuccos of the farm houses which seem to be ‘pure back-grounds.’ So visually, I am dazed, satiate [sic], purified and pleased.”11 In the south of France she entertained and socialized with artistic and literary minds from the Duthuit-Matisse family, friends Edwina and Barney Rubenstein, and the English poet David Gascoyne, to her farming neighbors and a favorite dog named Candy.

The tragedy of Jacobs’s story is that she died young in 1968, at the age of 41, of ovarian cancer. Jaffe and other artworld friends attended a memorial service held on September 12, 1968 at the Synagogue de l’Union Libérale in Paris. Her ashes were placed at Père Lachaise Cemetery where she joined kindred spirits Gertrude Stein, Colette, and Marcel Proust. Petlin honored Jacobs in the large-scale painting Rubbings from the Calcium Garden. . .Rachel (1969) held by the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the painting, two melting figures stand out against a dirty yellow sky—“a place of mystery,” as critic Jean-Louis Bourgeois wrote, rather than “a point of reference, perspective’s anchor.”12 Petlin intended his Calcium Garden series as a “visual mourning” for the losses of the Vietnam War and to friends lost concurrently.13

Given her maternal grandmother’s name, Rachel Jacobs was born on July 10, 1927 in New York City to Charles Alexander and Ethel Jacobs (née Rothschild), a Jewish family from Canada of Russian, German (Prussian), and Polish heritage. Once abroad, her brother Henry and her father—whom she addresses in letters as “C.A.”—supported her financially, as did many friends in France, foremost among them Francis. After passing through the hands of several friends in Paris, her treasured notebooks and manuscript drafts ended up with Francis. They are housed in his archive at the Getty Research Institute along with other projects slated for publication by Lapis Press, perhaps suggesting that Francis intended to (but never did) publish Jacobs’s papers posthumously.

In an undated letter to Jaffe, Jacobs wrote of a revelation about “the ‘new way of writing concepts’ [that] might possibly be extended further” to a critique of the social sciences and the subject of game theory. “If all this is possible,” she estimated, “then I shall have done something really worth while.”14 While Jacobs’s labors on these topics remained unfinished, her art criticism on Francis remains a significant contribution. Unlike “each sensible quality,” as she wrote of perception in the closing line to one of her exhibition essays on Francis, Jacobs herself was hardly “simple and still before disappearance.”15

—

Elizabeth Buhe is an art historian based in New York with expertise in expanded modernisms of the long twentieth century. She has taught at Fordham University and the Whitney Museum of American Art, and is a contributing critic for the Brooklyn Rail and Studio International. Her work has earned support from the Fulbright Program, the Luce Foundation, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Getty Research Institute, The Courtauld, and the Terra Foundation for American Art, among others. Currently, she is completing a book on Sam Francis and perception.

1 Rachel Jacobs to Yvonne Hagen, undated [c. summer 1959], Yvonne Hagen papers, England & Co Gallery, London.

2 Rachel Jacobs to Henry and Estelle Jacobs, 17 June 1965. Rachel Jacobs papers, New York; Rachel Jacobs to Henry Jacobs, 17 January [c. 1953], Rachel Jacobs papers, New York.

3 Rachel Jacobs to Henry and Estelle Jacobs, envelope postmarked 27 October 1959. Rachel Jacobs papers, New York.

4 Rachel Jacobs to Sam Francis, letters from 1958 and 1958, Sam Francis papers, Pasadena, California.

5 Rachel Jacobs to Sam Francis, undated [late 1958], Sam Francis papers, Pasadena, California.

6 Rachel Jacobs to Henry Jacobs, undated [1958], Rachel Jacobs papers, New York; Kenneth Sawyer to Clement Greenberg, 11 April 1955, Clement Greenberg papers, 1937–83, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 6 Folder 75.

7 Rachel Jacobs to Henry Jacobs, undated [1958], Rachel Jacobs papers, New York.

8 Rachel Jacobs and Yvonne Hagen, “L’académie délinquante,” Art d’Aujourd’hui 20 (December 1958): 36–38.

9 Rachel Jacobs to Shirley Jaffe, 16 September [1962], Shirley Jaffe papers, 1950s–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 2 Folder 14.

10 Rachel Jacobs to Henry Jacobs, undated [c. 1963], Rachel Jacobs papers, New York.

11 Rachel Jacobs to Shirley Jaffe, envelope postmarked 20 November 1964, Shirley Jaffe papers, 1950s–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 2 Folder 14.

12 Jean-Louis Bourgeois, “Irving Petlin, Odyssia Gallery,” Artforum 8, no. 5 (January 1970): 70.

13 Irving Petlin interviewed by Peter Selz, November 26–27, 2005, typewritten transcript, 17–18. Peter Howard Selz papers, 1929–2018, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 21 Folder 16.

14 Rachel Jacobs to Shirley Jaffe, 16 September [1962], Shirley Jaffe papers, 1950s–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 2 Folder 14.

15 Rachel Jacobs, Sam Francis, exhibition pamphlet (Paris: Galerie Rive Droite, 1956), [2].

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.